Language is THINKING.

It may look obvious and you would be quick to dismiss this as a trivial, “truthiness”- like statement not worth the seconds it took you to read it. However clear it may seem to you, it is connected to a concern that I had and that started to grow a few years ago as I engaged on Twitter education chats, particularly with primary school teachers. The trend, which continues to this day, is that we should simplify the texts students engage with, that we should select labeled books that are appropriate to each student’s reading level, and that we should have students analyze texts based on their interest or even to use pop culture sources because children find them “interesting” and because these texts appeal to their generation.

My argument against this trend is the same as it was years ago:

So while students should be given the opportunity to read at home any books they prefer, at school we should focus on high-quality texts that require cognitive effort, that enable students to acquire academic language, and that develop their aesthetic taste. Remember:

“Children grow into the intellectual life around them.” (Vygotsky)

On a similar note, academic language is *not* for school purposes only, for passing tests or for getting good grades. That is a fallacious argument brought by those who diminish its importance in everyday life. Take any newspaper, let alone any good book, and notice how background knowledge and complex language acquisition impact the very understanding of a text. I wrote about this extensively in my research blog (Who Is Afraid of Knowledge? and Stop Teaching Reading Strategies) but for the purposes of evidencing this take a brief look at the titles on New York Times today. You can easily notice how many words I boxed in, words that require a solid understanding of the concept they convey (“census”, “deployment”, “conscientious”, “ritual”, “abdication” etc.) – and that is only the semantic aspect. If we also consider the discourse, the complex usage of a word (e.g. “to divide” and “line”) then things get even more complicated (“The justices seemed divided along these lines.”).

What I find terribly dishonest is that the very people who benefited from a strong formal education, who had the opportunity to read high-quality books, who engaged with complex texts in their school years and in their profession are the ones who advocate for narrowing down curricula to suit children’s interest, including in the literature area. They speak of “broadening” reading while, in fact, the opposite is happening – students focus only on what *they* find relevant, a small chamber of ideas they enjoy, ignoring the broad cultural conversation they should be part of. The advocacy for a student-driven curriculum might stem from a well-intentioned agenda and desire to be innovative but it only erodes students’ ability to thrive in the Knowledge Age that relies more and more on *knowledge* (ah, the irony) and on the ability to deploy it creatively.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Now, on to the practical strategies I use in the classroom in literature classes. I selected them based on PRINCIPLES that research has proved over and over to be effective:

- Active retrieval

- Engagement

- Deliberate coached practice

- Feedback

Active retrieval (Jeffrey Karpike, Active retrieval Promotes Meaningful Learning, Association for Psychological Science)

“There are many learning activities that active retrieval could potentially be incorporated into. For instance, group discussions, reciprocal teaching, and questioning techniques (both formal ones, such as providing classroom quizzes, and informal ones, such as integrating questions within lectures) are all likely to engage retrieval processes to a certain extent.

Engagement, (Dylan Wiliam, Building Learning Communities, 2015)

“The most effective learning environments have three properties: they create engagement, they are responsive to student learning, and they create disciplinary habits of mind.

The research is now very clear: you have to do better than just telling the kids and you have to do better than just expecting the kids to discover things for themselves.”

Deliberate coached practice (Jordon Stobart, The Expert Learner, 2014)

“The most effective teachers often chose more difficult options, because they thought they were more interesting. They had a passion for their subject, they emphasized the importance of planning as a key part of their success. They saw class time as precious and allowed little or no ‘dead time’. Their focus was to get students to think – that was a key common factor to all of their strategies. These teachers strongly saw their role in the classroom as challenging students, putting a strong emphasis on having students to think, solve problems, and apply knowledge.”

Feedback (numerous papers, including this APA Historical Review)

“Whether feedback is just there to be grasped or is provided by another person, helpful feedback is goal-referenced; tangible and transparent; actionable; user-friendly (specific and personalized); timely; ongoing, and consistent.” (Grant Wiggins)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Back to the literature strategies that I use in class, I would like to clarify two aspects:

1 – We always read the same text as a class. Students’ only homework is to read a number of chapters daily that I assign. Daily reading is made clear to the parents from day one and I also ask them to engage in discussing the book with their children at home.

2 – The students can read other books at home and in their separate Library class with our librarian.

The most effective strategies that I used so far are:

- Literature Circles

- Textploration

- Socratic Seminars

- Quotation Challenge

- Matrix Connections

- Iceberg Thinking

- Side Think-Pair-Share

- Zoom-in, Zoom-out

WHY these 8 routines:

- They enable students to focus on the text, paying attention to its features, structural elements, vocabulary, ideas or cultural references.

- Students deepen their understanding by sharing their ideas with the group, having their ideas challenged and enriched as well.

- They help students develop all their language skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening.

- These strategies allow for both individual AND collaborative work.

LITERATURE CIRCLES

I am certain everyone is familiar with them so I won’t elaborate too much. I only use them for the first two months of school because I need time to observe my students’ language abilities and because the students need to gradually accommodate with the expectations that I have in literature classes.

FREQUENCY:

- Twice a week (usually at the beginning of the week and once towards the end so that the students have the possibility of reading several chapters and have richer conversations)

HOW:

- Divide students into groups of 5 and assign roles.

- Each student receives a new role in each session so that everyone has the opportunity to think about the text differently.

TIMING:

- 15 minutes – students skim/scan the chapters and write in their notebooks

- 20 minutes – students elaborate on their work, discussing with their peers

- 5 minutes – group reflection

- 5 minutes – group modeling (Fishbowl strategy)

*Group modeling: As students engage in discussion (stage 2) I walk around, listen, and record what students are discussing. I then select a group that stood out in that particular session – they might have used more complex vocabulary, they might have had more interesting ideas in relation to the novel, they might have used the “thinking moves” consistently (e.g. ”I would like to make a connection with…”). The students are invited to the front of the classroom to replicate their previous discussion as a group while the rest of the students observe; I occasionally pause the “fishbowl” students to emphasize for the rest of the class a particular phrase they used (e.g. “It was a remarkable passage because it reflected the anger character X had built.”), an unusual idea they generated and so on. It is important to EXPLICITLY do this because students really begin to incorporate academic language and to think deeper about the text – peer example is incredibly powerful.

TIPS

- Provide students with guidelines; everyone needs to be prepared in order to contribute

- Give scaffolds at the beginning until students use them automatically

- Insist on using academic language – students are not used to it and need to develop this habit (ask them to rephrase using the lists you provide them with; academic language is NOT natural and children need practice)

- Move around the tables – this allows you to actively listen to student discussion, to record positive as well as negative outcomes (say, great use of vocabulary or a misconception), and to show students that you *do* take their discussion as readers seriously.

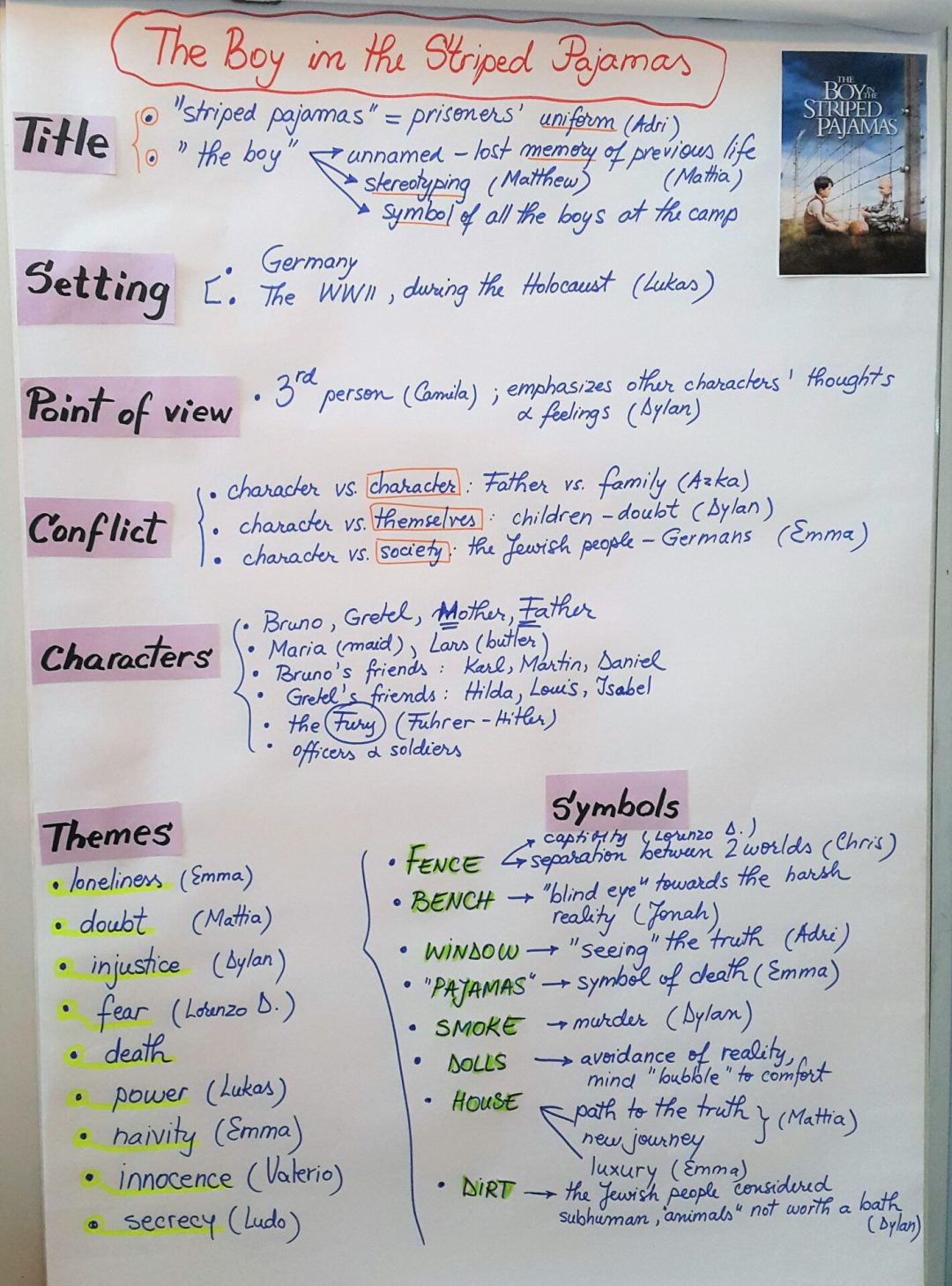

TEXPLORATIONS

These are whole-class novel analyses that involve knowledge of text elements. The students are invited to discuss them orally and as they share their ideas I write them on the flipchart.

Why are they effective?

- they develop text analysis tools that the students will be using independently later

- they stretch students’ comprehension of the text by noticing how different layers (conflict, dialogue, etc.) are used

- they enrich students’ aesthetic understanding by making clear contextual, metaphoric and even philosophical levels

I am always amazed at how important this way of building collective knowledge is in the classroom and how different ideas bouncing off enable children as young as 9 to come to love literature. It is a great feeling as a teacher to see their minds lit with awe when they discover how deep they can go with a text, something they have not done before. As this is framed as a conversation rather than a “thing to do”, they feel free to add their own insights, to build on each other’s ideas, and to challenge one another as well.

Just take the title of the novel Holes and the many ways the children could interpret it: they convey the hard work the teenagers had to do, the holes connect to the causes for their situation at the camp, the holes are a form of punishment for their previous wrongdoings, they are a tool to discover the truth of the past (“digging for truth”), they show the emptiness in the boys’ souls as they become accustomed to this tedious repetitive work, they are a place of danger as the deadly yellow-spotted lizards hide in holes seeking shade.

FREQUENCY: Once every two weeks (the students need time to read and notice how novel elements unfold)

HOW: Have students sit in a half circle. Use a flipchart to record their thinking. Have the key elements already on the desk (strips of paper where you write “title”, “conflict”, “setting” etc.). Glue one strip at a time; only after you feel they have exhausted that specific part (e.g. “title”, move on to glue the next strip (e.g. “setting”).

TIMING: There is no specific structure to this activity – since it is a whole-class activity, students engage orally in building ideas while you encourage participation by asking questions or using prompts (“I wonder how…”/ “Why do you think…?”/ “Let’s see this from this character’s perspective…”, “What if…?”).

TIPS

- Have the academic vocabulary displayed at the whiteboard: students need visual reinforcement of how to speak

- Display the flipchart in the classroom for the entire reading of the novel because students can add more ideas; a novel is a *conversation* never truly finished

- Encourage the students who are reluctant to share their ideas orally by allowing them time to write their ideas on post-its first

- Make sure the students know the narrative elements in a novel (I devote 2-3 sessions on this before embarking on our text explorations; I created a sheet for them to have at the back of the notebook in a transparent folder)

SOCRATIC SEMINARS

These are complex literacy events in the sense that students engage in individual and group work, they are required to use reading, writing, speaking and listening skills, have to provide feedback to their peers, and to reflect on their own contributions.

It is a routine that I apply after two months of school when the students already use academic language more consistently, understand the complexity of a text, and enjoy having deep discussions about literature. It is cognitively demanding and the students apply both knowledge of text and literacy skills intensely in these sessions.

FREQUENCY: Once a week (at the end of the week when several chapters were read)

HOW:

Divide the class into two equal groups: one group is the “inner circle” (below, the students sitting on the carpet), the other group is the “outer circle” (below the students sitting on the chairs). Each inner circle student has an outer circle peer that observes them and writes feedback on a post-it. At some point, they change roles – the inner circle students become the observers.

You, as a teacher, have the student names written on the paper the way they are sat in the circle. As the inner circle students begin to discuss, draw lines from one to another – that allows you to see who shares ideas more, who contributes less, how diverse the interaction is, etc. It will look like a web in the end (see photo). DO NOT interfere in the discussion at all – you are just a neutral observer.

TIMING

- 15 minutes – all students select 2 or 3 novel elements (e.g. setting, connections, theme) and write key ideas about each in their notebooks; they will develop them orally later

- 15 minutes – the Inner Circle students discuss their ideas; a Discussion Leader invites each student to speak; during this time, the Outer Circle students listen to their partners (who are sat right in front of them) and write their feedback

- 15minutes – the Outer Circle students become the Inner Circle and discuss while their partners write feedback

- 5 minutes – the students read the feedback they received and then self-reflect in their notebooks.

Finally, share YOUR web diagrams so that each group can see how they interacted. This is a powerful visible strategy for the student to literally see the actual number of contributions they had during the session, and it can help them set a goal next time (e.g.”I only contributed twice so next time I will try to be more engaged.”; or “I think I was quite dominant in the discussion so next time I will allow others to speak more.”).

TIPS

- Again, have the academic language displayed at the whiteboard so that the students can use it quickly

- Have lists of conversation moves and feedback prompts printed for each student to use in the session

- Model the first Socratic Seminar so that the students can understand the structure, grouping, and expectations (you can also show a YouTube video of such a seminar)

- Highlight good aspects of each session so that the students can feel your interest in their thinking as readers (e.g.”I particularly enjoyed how most of you focused on the connections between the themes in this novel.”; “It was great to listen to the way you used sophisticated vocabulary today.” etc.).

Although Socratic Seminars are usually implemented in higher grades, they worked incredibly well with my students for years now. I made this move when I participated in a category 3 IB workshop on literacy, Reading and Writing through Inquiry, and where the workshop leader told us that his school used this format starting with…grade 3! It was a whole-school approach and its effectiveness was clearly demonstrated through the pictures of practice he shared with us (samples of student writing and videos of students engaged in such seminars). So do not hesitate if you think it is too early – it is effective if you implement this strategy correctly, if you are consistent in using it (so that it becomes a class routine), and if you have high expectations from your students (while supporting them by providing scaffolds at first).

*Part 2 of this post is here (the other 5 strategies plus PDFs you can download)

thank-you so much for such an explicit explanation of your refined teaching practices, Cristina !

Thank you! I am glad that you found it helpful, Heidi!

Thank you for taking the time to blog about this. I appreciate the structured way you’ve shown how these learning strategies develop. I feel empowered when I read your work:D.

Thank you!

Just found this today. Thank you for such detailed explanations of each strategy. I will be using these for my Spanish 4 honors class!